USGTF Members Recall Meaningful Encounters with Students

“ There is no type of miracle that can’t happen at least once in golf.”

– Grantland Rice (1880-1954), American sportswriter

Every instructional occasion is special. Lessons are given with goals of developing game improvement, confi dence, and refi nement of technique. Students come in groups or as individuals, for single sessions or long-term series, in all age and skill ranges. Progress is made and celebrated, enthusiasm instilled or restored.

Sometimes, though, certain teaching moments arise in which golf instructors fi nd they have the

chance to make a signifi cant and lasting difference in the games and lives of students. The opportunity

to help a player rise above personal challenges to achieve success is the stuff teachers’ dreams are made of. USGTF members seem to have no shortage of such opportunities and contributions.

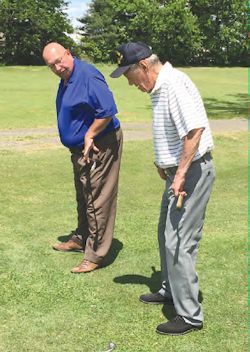

Cole Golden (right) demonstrating proper alignment with Mark Harman.

Praiseworthy Instruction

“The true defi nition of teaching is communicating well with people,” says Cole Golden, USGTF Master Teaching Professional and International PGA member. “The more you’re in it, the more you learn. I learn every day I teach.”

Golden, who has taught in places as farfl ung as India, Mexico, and Canada, has his own golf company, Golden Golf, in Wichita, Kansas, and also is a business consultant at Patterson Dental. One of his favorite teaching memories stems from when he was conducting a golf school in Oscoda, Michigan, in 1998. Three of his students were women in their mid-40s. Although they were not avid golfers, they took instruction well and seemed happy with their improvement. Four weeks after the school’s conclusion, Golden received a phone call from one of them, who told him that although her handicap was 25, in a pro-am with her husband and their club pro she had shot an 82, their team winning the pro-am by a wide margin.

“People thought she was cheating,” Golden says. “Even her pro couldn’t believe it.”

In fact, says Golden, her home pro swallowed his ego, telling her she needed to stay with the instructor who was responsible for her progress. As a

result, the three ladies, who had met for the first time at Golden’s golf school, followed Golden for several years to the schools he taught in various locations.

“I learned from that experience,” Golden says.

“In the same circumstance, I always praise other instructors.”

Bill Nightingale, USGTF Master Teaching Professional, has a treasure trove of golf-instruction memories. He taught for many years at GolfTEC in East Hanover, New Jersey, and at the driving range at Anchor Golf Center in Whippany, New Jersey. As head of the Nike Learning Center at Desert Rose Golf Club in Las Vegas from 2003-2005, Nightingale started a junior-golf school which drew students from diverse races and cultures.

Bill Nightingale with a group of his Junior-golf school students at the Desert Rose Golf Club in Las Vegas,Nevada (2005).

“That’s what we are all trying to do in the golf industry: Bring golf to all kinds of people,” says Nightingale.

Now retired from his business career and formal golf teaching, Nightingale appreciates the children’s diverse backgrounds at The First Tee chapter in Newark, New Jersey, where he assists.

A memorable teaching experience for Nightingale was with one of his students, Bruce Hoppe, who signed on as a beginner at Anchor Golf Land and stayed with his instructor for many years. Today, Hoppe plays to a 9 or 10 handicap, and has become a good friend and golf partner to Nightingale.

“Bruce was very loyal to me,” Nightingale says, “and these days we play golf together quite a bit.”

USGTF member Leo Perlmutter

A USGTF member since its inception in 1989, Leo Perlmutter actively teaches over 400 golf students every summer in the New York City Parks &

Recreation Department. With a degree in business management, Perlmutter clearly possesses people-management skills, too. One of his best stories dates from when he was teaching at a popular golf school in Vermont. The busy facility offered a 5-day golf school Monday- Friday. One student, Helen, was in tears after the fi rst day of instruction and, concluding that she just couldn’t do anything right, asked to be transferred to another instructor for the following day, which is how she came to be Perlmutter’s student.

“This, of course, must have been a problem with the teacher,” says Perlmutter, “because as we all know, golf is not cancer research. It’s a game and it should be fun.”

For the remainder of the week, Perlmutter encouraged Helen, complimenting her on some of the things she was doing correctly. Realizing she was on vacation, he tried to make the entire learning experience as pleasurable for her as possible. Soon she was getting the ball airborne, using all the clubs in her bag and enjoying the game.

“Looking back, this certainly was one of my most memorable teaching experiences,” Perlmutter says.

USGTF member Woody Hoover

Sometimes an instructor can pinpoint the pinnacle of his teaching career. For USGTF Master Teaching Professional Woody Hoover, it came in 2007.

Every Sunday for fi ve years, Hoover worked with Raymond Earl Allen at a driving range run by Denham Springs Park and Recreation in Denham Springs, Louisiana. Twenty-fi ve years old when his golf lessons began, Raymond, who is autistic and has other special needs, faced a challenge in verbal communication.

“His speech was more of an expression of how he hit the ball than actual words,” Hoover says.

It took one year until Raymond succeeded in hitting the ball off the ground. The duo’s patience was paying off.

Then Hoover heard that a golf pro at the Baton Rough Recreation Department, who had a specialneeds child, was putting on a special-needs clinic for four consecutive Sunday afternoons, to be followed by a skills competition. Every Sunday, Hoover drove Raymond to the clinic, assisting with instruction including posture, how to hit, putting, chipping, driving… working backwards through the skills.

Raymond, the oldest competitor in his group, won the driving and chipping competition and was awarded a small trophy.

“It was nothing spectacular, but we were both proud,” says Hoover. “It was my best moment as a golf instructor.”

Woody Hoover and his Denhan Springs High School golf team after their 4th-place finish in the Louisiana state tournament (5A division).

Retired from his career as a purchasing agent for Turner Industries, the largest petrochemical construction company in the southeastern U.S., for the last three years, Hoover has been a non-faculty coach for the Denham Springs High School boys golf team. In 2013, the team tied for fourth at the state tournament in the 5A division, the biggest in Louisiana.

“It was another proud moment,” says Hoover, who in 2006 co-founded the Future Athletes of Louisiana to assist young golfers get started in the game. In 2014 the non-profi t lost its funding, but Hoover is not deterred from his desire to share his golf knowledge with others.

Bill Baldes (left) working with a student on hand position during a lesson a the

Tappan Golf Center in Tappan, New York.

For Bill Baldes, USGTF Master Teaching Professional, experience proved invaluable. Having been introduced to golf at age 14 as a caddie in Carmel, New York, he developed an early love of the game. Teaching became his second career after having retired in 1995 from AT&T. As an adjunct professor in technology for telecommunications at a local community college, Baldes learned someone was needed to teach golf at the college.

“I soon abandoned teaching technology,” says Baldes, who these days donates lessons to a local high school and gives lessons at a local range.

The experience Baldes was to draw on for his memorable teaching moment was with Special Olympics. Teaching golf to teenaged Special Olympians, Baldes found they appreciated him watching them closely. They didn’t always understand instructional details, but they enjoyed the attention, the lessons, and their successes.

In 2008, a friend referred Blaise, a gentleman in his mid-50s who suffered from Parkinson’s Disease, to Baldes for golf lessons.

“As compared with teaching Special Olympians, this was different,” says Baldes. “Blaise knew exactly what was happening.”

Baldes says he relied on instinct and experience to teach Blaise, whose main challenge was with balance. What are we looking to do? What are our expectations? These are the questions Baldes asked Blaise.

“I want to hit the ball better and play well,” was Blaise’s reply.

Baldes had some tricks up his sleeve. They talked about balance and worked on it together. Baldes helped make Blaise more conscious of where his weight was, the position of his feet; he had been swinging too fast to protect his body for fear of falling. They needed to slow down his swing. Blaise had been working with a specialist on balance and told Baldes about some of the drills he was doing. Baldes asked Blaise to employ some of those drills while swinging. His swing improved right away, but he still needed to get it under control. When the pair worked on tempo, so that Blaise would stop swinging dramatically fast, he started making good contact with the ball.

Bill Baldes (left) and student at the Tappan Golf Center in Tappan, New York.

“I learned a lesson here,” says Baldes. “Special Olympics kids were happy with anything you showed them. But with Blaise, people were afraid to look at him, and he apologized.”

Inexperienced in this situation, Baldes realized it was his own fear of embarrassment that was getting in the way. He got over it that very day, he says.

“I had a shift in my thinking,” says Baldes. “I realized I couldn’t help Blaise unless I stared at him to assess his progress, just the way I paid attention to the Special Olympians. He expected no less. Otherwise, how could I help him?”

Blaise remained Baldes’s student for four years. Much improved now, with his symptoms under control, Blaise plays golf on the course these days.

He mentioned to Baldes how much he appreciated his patience.

“I told him,” Baldes says, “that if I didn’t have patience, I wouldn’t be a good teacher.”

To Baldes, the gratifi cation he derives from teaching golf is part of the payment. Having taught Blaise brings a special sense of satisfaction.

“A lot of my lessons are memorable, although they don’t always stay in my head,” says Baldes, 72. “But teaching Blaise did.”

Skip Shaw (left) and student working on swing alignment.

Skip Shaw, Master USGTF Teaching Professional and course examiner, has many stories to tell, but one stands out. Fifteen years ago, a gentleman named George, then 55, brought his 7-year-old grandson, Austin, for a golf lesson where Shaw was teaching in Ohio. The boy already showed some skill; Shaw asked how he had learned golf so far. Austin replied that his grandfather had taught him.

“Talking to George, I learned that he had played golf until he had a stroke, ten years before,” Shaw says. “His left hand couldn’t stay on the golf club any more, so he gave up the sport.” That didn’t prevent him from teaching his grandson, though.

The two men became friends. After giving a couple of lessons to Austin, Shaw had an idea for his granddad.

“I took a 7-iron to my shoemaker and asked him to sew some Velcro onto it,” says Shaw. “I didn’t tell George I was doing this.”

Bill’s Cobbler Shop in Canton, Ohio, would become an important part of the story. Using a regular golf glove, the shoemaker also sewed Velcro on it in just the right places. After one of Austin’s lessons, Shaw pulled George aside and presented him with the 7-iron. George was reluctant.

“Let’s give this a shot,” Shaw remembers telling George. “You taught your grandson so much. Austin never asks a question; he has blind faith. Let’s try it.”

George’s fi rst ball was dead straight but low. “My hand didn’t hurt,” George said. After 45 minutes, he was hitting the ball 100 yards in the air.

Shaw bought a light set of women’s graphite golf clubs and took them to his shoemaker, who placed Velcro on every club where it needed to be, using a special rubberized cement and applying it with heat on the grip of each club, and also sewing Velcro on the golf gloves.

After receiving the special set of clubs, George often would take them back to Bill to replace the Velcro when needed.

“I’ve known Bill, my shoeman, for fi fty years,” says Shaw. “He never charged me a dime for any of this.”

Skip Shaw (left) and student working on proper posture.

Fast-forward 13 years. Shaw saw George at Raintree Country Club in Uniontown, Ohio, where Shaw has been an instructor for the past eight years, teaching students ranging in age from three through 72. (“The three-year-olds listen better,” Shaw says.) George had Velcro on his clubs, saying he had been playing often but had to cut down to three times a week because he was getting older.

“We hugged and cried,” Shaw recalls.

Suddenly, a tall, handsome young man approached them and said brusquely to Shaw, “Hey, big baby, move along. We are ready to tee off.”

Taken aback, Shaw replied, “This guy (referring to George) means something to me. Don’t talk to me like that.”

“I’m Austin,” the young man responded with a grin. “I can talk to you any way I want.”

After Shaw, who has Parkinson’s Disease, recovered from the surprise, the three of them played nine holes together. George died shortly thereafter in an automobile accident. He was 72.

“It was wonderful to see George and Austin again after all those years,” says Shaw, now 57. “As for me, I’m still around golf, still happy, enjoying life.”

One might think this is the end of the tale. Not quite. Shaw extends the story by mentioning Edwin Shaw Hospital in Akron, Ohio (no relation), there many people go to rehabilitate from strokes and disabilities. A golf program had been part of the opportunities there to assist patients with hand-eye coordination.

“They found out about the Velcro,” Shaw says with a sense of pride. “I think George told them.” The Velcro idea is one of the hospital’s therapies now in its golf program.

“I honestly think George did more for me than I did for him,” says Shaw. “Just the look in his eyes when he played golf for the fi rst time with his grandson, who had never seen him play, gave me goose bumps.”