Statistics Shaping New Way Coaches Look at Golf Success

An article in the Spring 1999 issue of Golf Teaching Pro, titled “Statistical Analysis: Surprising Conclusions”, pointed to a study in a 1987 issue of Golf Digest that showed greens in regulation was the most highly correlated statistic in overall scoring average. Of course, this flew in the face of accepted convention that the most important factor to good scores was the short game and putting.

A number of USGTF professionals disagreed with the conclusion, insisting that a good short game was the key to good scores, They pointed to the fact that golfers are always going to miss some greens in regulation, and to save par, a good short game was necessary.

A new book by statistician Mark Broadie has come out, based on in-depth statistics the PGA Tour keeps, called Every Shot Counts. Going deeper with statistics not available back in 1999, broadie confirms that tee-to-green prowess is much more important to overall scoring average, while short game and putting contribute only somewhat.

A Look at the Past

A Look at the Past

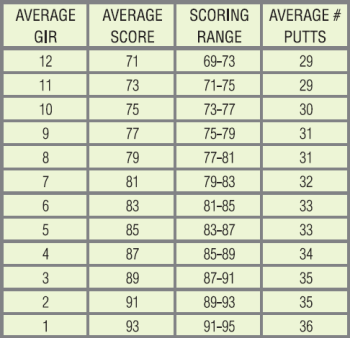

Let’s revisit what we knew in 1999. If you know how many greens in regulation a golfer averages, you would know within two strokes someone’s scoring average range. The table (right) based on a 72-par golf course, is till valid today.

Please note that this table deals with long-term averages (20+ rounds), not individual or even a few rounds. Of course, it’s possible in a given round of golf to hit only five GIR and shoot under par, or to hit 12 greens and fail to break 80. It’s also possible for a professional in a four-round tournament to average 10 GIR and average 67 each day – these things happen, and we’re not saying the short game and putting are unimportant. You most definitely can save strokes during a round of golf if your short game and putting are superb that day. However, over 20 or more rounds, if you know a person’s average GIR, their average score on a par-72 course will be within the scoring range listed in the table. Believe it or not, there will be virtually no exceptions to this.

Using the Table

We, as teachers and coaches, can use the table to see where our players need improvement. For example, if we have a student who is averaging 93 while hitting 2 GIR on average, they can cut a maximum of four shots by sharpening up their short game, although improving the maximum is a tall order. If this same student is already averaging 89, in order for them to improve, they must get better from tee to green. Telling this person they can start shooting in the mid or low 80s by improving their short game does them a grave disservice, because it’s frankly impossible. And yet, how many times have we heard teachers say the best way to cut five strokes off your average score is to improve your short game? Countless times, but the fact is, it’s a myth.

Well, let’s qualify that. It’s a myth for someone who can average at least one GIR per round. For those who are, say, averaging 95 or more, they can indeed cut quite a few shots from their average score by being better on and around the greens. However, once someone is able to average 1 GIR, improvement will come mainly through hitting the ball better.

You might ask, “How come someone who averages 7 GIR, for example, can’t average in the low to mid 70s? After all, if they can get up and down 6 out of 11 times, that’s only five bogeys, and if they can average even one birdie a round, that means they’ll average 76.” That sounds good on the surface, but the answer is that golf skill is relatively similar throughout the bag. In other words, you won’t see someone who hits the ball like a typical 81-shooter (someone who averages 7 GIR) with a scratch-level short game every day (6-for-11 in up-and-downs). More likely, they’ll only get up and down 4 out of 11 times (7 over par), 3-putt another time (1 over par), and on the 11 greens they miss, once or twice take two or three more strokes to reach the green than in regulation (2 over par). Offset this with one typical birdie during the round (1 under par), and they have an average of 81 (9 over par), ±2 strokes.

The bottom line is the most important shot each hole is the first one we have once the green is within reach. That shot is hugely important in determining our scoring average in the long run.

New Research

Broadie’s research shows that approach shots are 40% of a person’s average score; driving 28%; short game 17%; and putting, 15%. However, when it comes to professional tournament winners, 35% of their score is determined by their putting, so we can surmise that short game and putting are more important to an individual round of golf or tournament than they are in the long run for overall average. It is for this reason that short game and putting are not unimportant and must be practiced. But, keep in mind that players at a certain level are at that level because of their ballstriking, not their short games.

One way to look at this is for us to say that the tee-to-green game provides the stability in scoring; short game and putting provide the volatility. Let’s go back to the example of the average 81-shooter who averages 7 greens in regulation. Suppose we do the following experiment: Our 81-shooter hits all the regulation shots, and then noted short game and putting artist Luke Donald takes it from there. What would likely be the average score?

In 2013, Donald ranked 22nd on tour in scrambling, averaging saving par 61.5% of the time he missed the green. Out of 11 greens missed, this would be about 7 pars saved. That’s 4 bogeys. Add the couple of extra strokes Donald is likely to take in reaching a missed green in regulation, thanks to a penalty or impossible position the 81-shooter puts him in. Now we’re at 6 over par for the round. Donald averages making birdie 30.8% of the time he

hits a green, so that’s 2 birdies for the round. Final score: 76.

So yes, it’s possible for an 81-shooter to cut 5 strokes off his average score through short game only – that is, if he develops the world-class short game of Luke Donald. Now ask yourself, is that realistic? Of course not. And, we can see that the score of 76 is closer to the abilities of an 81-shooter than a tour pro’s, further telling us that tee-to-green is more responsible for a person’s score than is the short game.

Using Statistics to Help Golfers

A golfer’s tee-to-green ability determines their scoring average over the long term, while their short game and putting determine how well they do within their ballstriking class within a 4-stroke range. Some days the ballstriking will be a little sharper, the short game and putting outstanding, and the score will be several shots better than average. Conversely, some days it’s the opposite. But, in the long run, it all averages out.

As coaches, it’s imperative that we use statistics to help improve the scoring abilities of our players, because they tell us the strengths and weaknesses of our players with no subjective bias.

One way for coaches to use statistics is to divide up their competitive players’ rounds into two categories: better than average and worse than average. Comparing the statistics of the two categories will tell us exactly what the statistical differences are between good and bad performances. Some players might be more volatile in the short game; others, in the long game.

At a minimum, we need to know how many fairways were hit, the number of greens in regulation, and the number of putts on each hole (which also tells us the up-and-down percentage). Going deeper, you can have your players record what clubs they hit with each shot and the results.